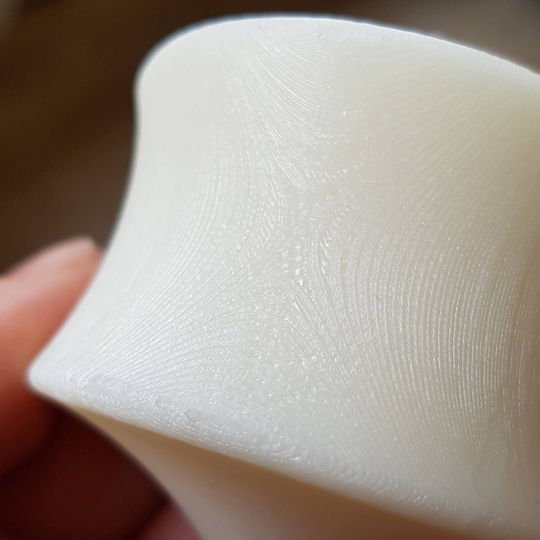

Click the images for full size

Teaching 3D printing

Rapid Prototyping in perhaps a misnomer. Sure, it’s faster than the traditional forms of prototyping, but ‘rapid’ belies the hours and hours of digital sculpting it takes to get a set of pixels to look like the thing in your brain, and then lined up in a way such that a computer can turn them into something physical. This is was one of the stumbling blocks I aimed to prepare students for in this RMIT University elective course: 3D Printing for Beginners.

The course accepted students from all over the uni. This meant that we had to start right from the beginning with lectures on theory and knowledge: the history of 3D printing, where it sits within contemporary manufacturing, the different types of printing, and the different types of materials available (and what you can and can’t do with them). And we covered other adjacent basics, like 3D scanning (aka helping a machine interpret a physical form) and photography (aka how to best present your designs to highlight your work).

Meanwhile we used practical critiques and machine time to built that all-important way of thinking that helps students think in digital 3D. It’s that translation that occurs between what I think I want to make, what it looks like and how it works, and how the computer needs it to work to produce a print. It’s more than a visual language - it’s mechanical and structural, as well as that fuzzy interpretation of a program’s UI to action.

Think about it: in order to print a physical form I need to visualise the form in 3D in my mind. I need to communicate that vision to a piece of software, interpreting what the software offers me and the limitations it has to the form I have in my head. I need to fill the gaps between something I imagined to how it’ll work in the real world. Depending on the form, I might need to segment that form into printable sections to be assembled later. Or, depending on what the form is used for, I might need to consider the print as a first step in other manufacturing processes (like printing a mold for casting, for example).

These considerations come (relatively) easily for students studying related fields like architecture or engineering. For those studying economics, psychology or law, for example, these are fundamental skills that are a far cry from their normal ways of thinking that need to be built and strengthened before they can hope to print something functional.

In guiding and grading student’s work I took this into consideration; how much of a mental leap did they need to make to produce a physical object. Accordingly, some students created basic forms in free online CAD software. Others used this course to contribute to their honours projects in industrial design and architecture. The challenge for me was to not only quickly understand a student’s context and ability, but to help them use this course to fill a gap in their knowledge and to push their capability beyond their normal: to help them learn.

I loved it.

Why include redacted images?

I think it's important to capture the realities of the experiences I design - which inevitably include sensitive information - while respecting the anonymity of those involved and safeguarding the business-relevant information shared during these experiences.

(I also like the way the visual representation reflects the vagaries of memory. There is a surreal quality to the images I find quite attractive...)

Want to know more?